Happy Sunday!

It’s taken me longer than usual to write this post.

I’m back on my reflective bullshit, and that takes more time and care.

Today’s post comes with a rare trigger warning. This essay contains discussions of sexual assault.

It also features 2010s fashion, which is enough to send anyone down into an anxiety spiral…

Let’s get into it!

Kesha’s Tits Out Tour transformed me.

I openly sobbed several times.

I talked about it with my therapist.

I’ve spent two weeks dissecting all I could possibly say about this show.

And now I am coming to you, braided feather hair extension in hand, to share my musings.

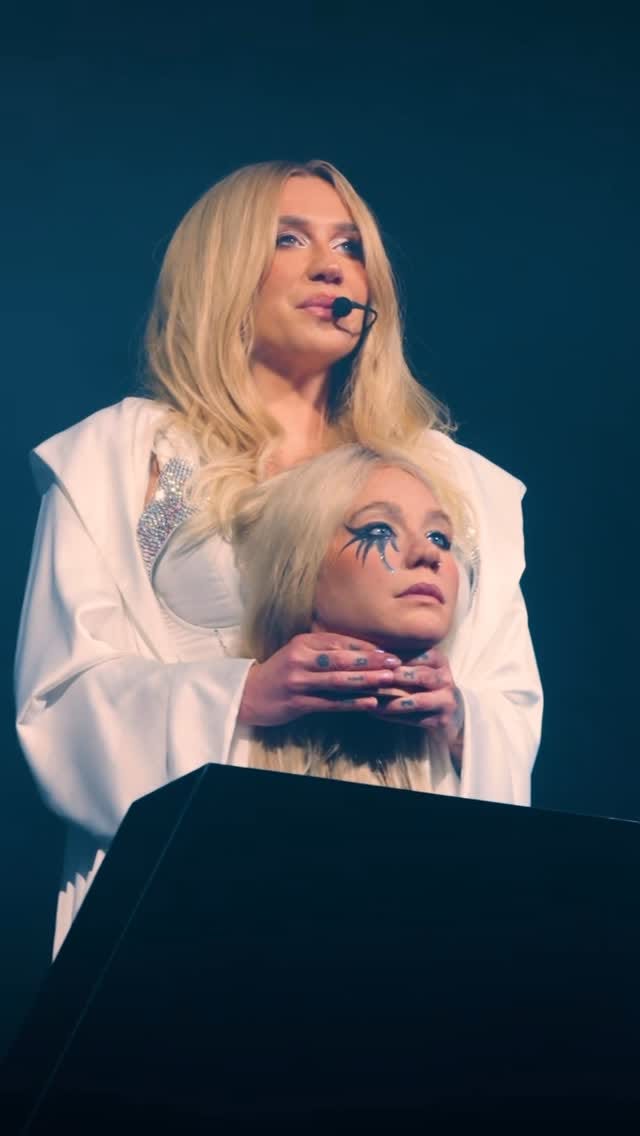

I knew we were in for a ride when she came out carrying her severed head.

TiK ToK started playing as she set the tone for the show: “We do not stand abuse in my house, so middle fingers up. You know what to do.”

Without pause, the whole crowd screamed, “Wake up in the morning like fuck P Diddy.”

A moment that was somehow both empowering and hopeless.

Because she changed her own song to call out his behaviour.

Because 16,000 people affirmed those survivors’ stories at once.

Because Diddy was found not guilty of the most serious charges.

Kesha continued the set, letting us know that she’d remixed all of her music to play live. This way, we could enjoy the show without Dr. Luke profiting.

We cheered, but I was frustrated. I couldn’t reconcile that over 10 years later, her abuser’s fingers were still smudged over everything.

That was the first time I cried.

Throughout the show, I recognized that Kesha was the backdrop to my coming-of-age.

In grade 10, my best friend and I listened to her first album in the darkroom of our photography class.

We felt adult singing naughty lyrics about sex and parties, thinking one day, we too would be at a hole in the wall, a dirty free-for-all. That it would be fun and freaky and all the magical grungy things her party anthems promised.

Only it wasn’t.

The reality was scary and messy.

We got taken advantage of. Made bad decisions. Drunk cried. Chugged flavoured vodka and woke up with physical bruises and emotional wounds.

By 2014, we weren’t friends anymore.

I was in university, and Kesha’s legal battle with Dr. Luke had just begun.

As a new adult, everything started to look different.

The high school nights out that didn’t feel safe. The drunk detachment that came after. The friends who called me “the group slut” without pausing to ask how or why sex had entered my life so quickly.

With Kesha, it was so much worse.

I watched the public scrutinize every detail of her case. Girls could not write party music and be raped. As if one thing encouraged the other.

"Any reasonable person will not believe her," Dr Luke said under oath.

As #MeToo took over my newsfeed, Kesha was already a cautionary tale about speaking up. She was a caged pop star, forced to create art for the same man she accused of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and emotional abuse.

Her story made it clear that there were good victims and bad victims.

There was no space for anything in between.

You couldn’t have a reputation, a promiscuous phase, or an inconsistent story. You can’t have reached out after the fact. You couldn’t be unsure.

You must be the ideal form of a survivor unless you’d like to be doubly punished.

The Tits Out Tour revels in messy contradictions.

The show embraces being Boy Crazy and a survivor on the same stage, living out the Madonna-whore complex in real time.

Kesha shreds on guitar.

She pretends to murder a dancer in jest.

She sings an emotional ballad about forgiveness that brings the crowd (namely me) to tears.

She gets thrown around the stage in a straitjacket singing experimental music about an acid ego death, part performance art, part pop act. 1

She floats in the air with a giant halo and a prayer on the big screen.

She puts on a corset and panties to go for a joyride.

Yesterday, I listened to an Esther Perel podcast about grief.

“You need to do both. You need to deal with the trauma, and you need to engage with life.”

I’ve never seen anything accomplish this better than Kesha’s performance.

I’m in awe of the gumption it takes to tackle the industry as an independent artists after such public shaming.

The way she can simultaneously be playful and share the darkest parts of her life.

The way she can ask for attention and call out the exploitative elements of her own fame.

To call it inspirational is an understatement. I cannot believe the amount of solace I took from a show that was widely attended by drunk teenagers and men in G-strings.

I guess you never choose what will be your salvation… or what you’ll be wearing when it comes.

Part of the impact is how rare it is to see survivors celebrating.

I’m exhausted by stories of predators becoming presidents and Supreme Court judges. Friends posting videos at the Chris Brown show.2 Hockey culture existing

There is a familiar path of standing with women, only to be cut off at the knees.

Where else have you seen a survivor talking about their healing in a big, triumphant way?

No one else is throwing a party that acknowledges their sexual assault!

Rape is typically a shameful thing to forget. Healing is individual and internal.

A burden you don’t share with the world.

Something typically left for quiet self-discovery and reflection.

In university, I studied ‘great books’ and philosophy. Between keg stands, I read ancient texts obsessed with how to ‘know thyself.’

(Yes, I’m about to compare Kesha to Socrates)

Everything we learned was about living virtuously, the ultimate and universal pursuit of how to be. But ancient philosophers didn’t know what it feels like to be unsafe in their own bodies.

To have it play tricks on you.

To have it open for something that fundamentally did not want.

To not understand why you didn’t fight back.

When they talk about the ‘good’ and ‘virtue’, they aren’t considering the goodness and virtue that can be stolen.

They aren’t factoring in the definitions that are layered on top of victims. How a survivor’s identity can be twisted into knots.

They focus, instead, on output. Living a ‘good life’ means living in accordance with your role in society.

But what does that mean when you believe you are at fault?

When you’re told you’re a slut?

When someone else’s actions have defined how the world sees you?

When knowing yourself and your role also means reckoning with the terrible, awful thing that happened to you?

Recently, I’ve been seeking out philosophical theories on what sexual assault does to the self. So far, I’ve come up empty.3

What Kesha presented was the most nuanced survivor journey I’ve seen.

Within each set, she created pockets for sadness and anger. She had us explore the stages of her grief together, allowing for a huge release by the end of the show.

She cued up her last set, saying, “I’m going to put on a slutty outfit, and we’re going to celebrate my freedom.”

For her encore, she sang Praying and Cathedral, songs that speak to different parts of the healing process.

Allow me to dive into the scripture…

Praying stopped me in my tracks in 2017. This was the #MeToo anthem we all needed:

The most religious I’ve ever been was singing along to this chorus, wondering if my rapist understood the gravity of his actions.

If it would make me feel better or worse if he did.

If I could see myself as more of a victim if he co-signed on the rape.

Praying helped me recognize that it didn’t matter. It’s about forgiveness rooted in resilience and stoicism — the kind of letting go you need to move forward.

Cathedral is the internal step of this journey.

I'm the cathedral

I'm finally coming home

Oh, God, it feels good

I'm the savior, I'm the altar, I'm the Holy Ghost Every second is a new beginning

I died in the hell so I could start living again

In the cathedral

This is a song about being your own salvation. Your own peace.

It’s about finding a sanctuary within yourself and your body.

It also speaks to the violence of healing. How an older version of herself had to die so she could create a new image of herself. One that isn’t doused in the trauma.

This is something beyond self-knowledge. It’s the full destruction and rebuilding required for self-acceptance.

Together, these songs felt like finality. The culmination of a decade-long healing journey that took absolutely everything she had to give, and that she was kind enough to share as proof that there is an end.

I cried the whole way through.

I cried for her.

For all the extra work and extra time and extra tears she had to put into her career to be cleansed from what he did.

I cried for all the other survivors in the crowd.

For everyone who put themselves out there, faced public degradation and slander, only to find more pain and disappointment.

For all my friends who have similar stories.

I cried for myself.

For the tween version of myself who thought Kesha's lyrics were risqué and who didn’t know that sex could be hurtful.

For the high school friends I lost because they couldn’t comprehend what I was going through.

For all the work I’m still doing, almost 15 years later, to process it all.

I let myself cry and cry and cry.

Because I needed it.

And because smudged mascara matched my outfit.

Y’all, what the fuck is happening here?

I’m still looking! Smarter people than me, please send whatever you have