Happy Thanksgiving!

I’m trying to spend more time reflecting on past work. This blog’s archives are deep, dark, and ready to be mined!

Remember the eel pit?

Remember the Britney puns??

Remember the extreme and palpable depression of 2021?!?!

I’ve produced a rich history of text, and I’m ready to unearth its spoils!

Today, I’m revisiting a post from September 2023.

My grandmother is still kicking it (potentially out of spite at this point, it’s hard to say), and it’s only gotten more bleak from here.

If you’re spending the holiday with an unwell loved one — this goes out to you!

Fast Socks & Forgetting

“Leave me here,” my grandmother instructed from the floor.

I held her by the armpits as she scooched onto the nearby step. Defiant, but wincing with effort the whole way.

“I’ll help you up,” I said, and she glared at me as if it was my fault she was down there.

As if I hadn’t caught her fall.

She’d only made it four steps before collapsing like a Twizzler.

This was the most physical contact I’d had with her in years.

We are not a touchy-feely family, and, despite my grandmother’s accusatory stare, we didn’t have a habit of tackling each other to the ground.

I tried to coax her up. She ignored me.

She’d rather perch on the stoop for hours than have me lift her.

Dementia will eliminate all of her motor functions before it reaches her pride.

We stayed in our deadlock while everyone else packed up lunch.

She put her head in her hands, and I stood uselessly on the deck, looking inside toward the dining room.

The table was missing a chair.

Her chair.

My grandmother always sat closest to the back door, often reaching behind herself to let out the dog.

We’d moved her seat when we got here to clean up after Honey, the yellow lab who had waited at the door until she couldn’t hold it anymore.

My grandmother either hadn’t noticed or hadn’t made it on time.

She would fill Honey’s bowl a dozen times a day, but never clued into the stench.

“I feel sick,” she said, and I did, too.

I remembered when she used to orchestrate the entire family get-together. She would make decadent meals and buy too many desserts for our six-person family. On Christmas, she would host two dinners and a brunch.

We’d have leftovers for weeks.

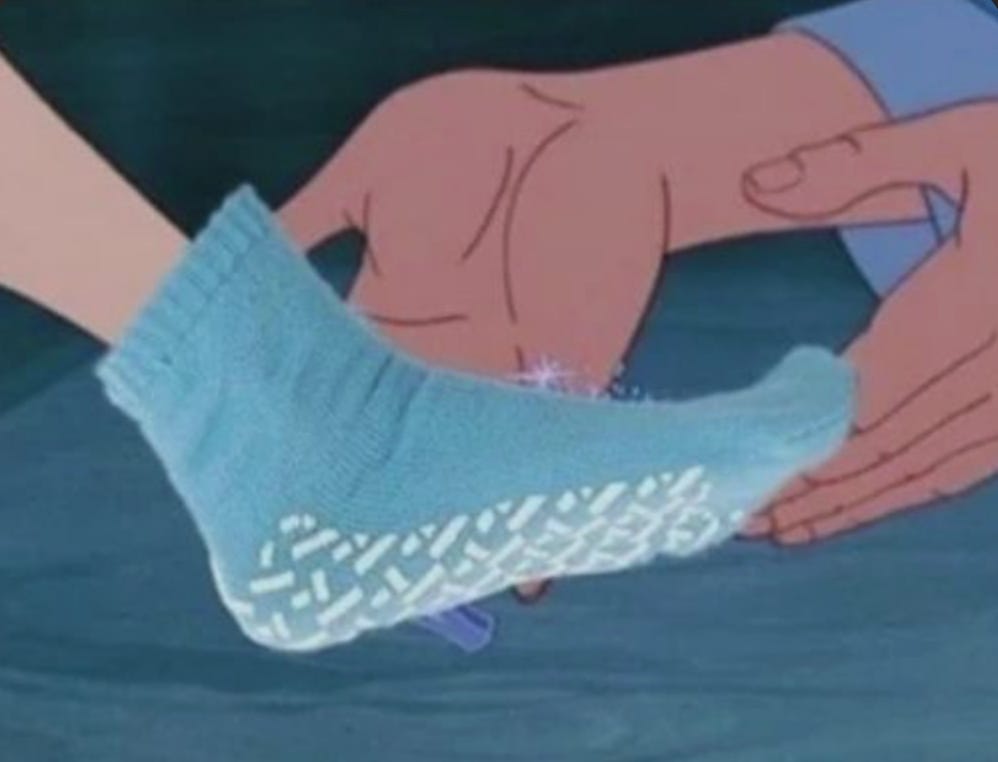

While she prepped, I would run around the house sneaking treats and pestering my uncles. I sprinted around the sharp kitchen corners at full speed in socks with rubber grips.

Go-Fast Socks, we called them.

“Go, go, go!” my grandmother cheered while putting out a shrimp ring, a cheese board, or a cookie tin.

Possibly all three.

Definitely all on themed plates with themed napkins.

Today, we’d eaten pre-made sandwiches and monitored her intake. She could never remember if she was full and gave herself almost as many treats as she gave Honey.

“Slow down,” my grandfather had told her 10 minutes ago, “that’s enough.”

“I think I’m going to throw up,” she said, not looking up.

My mom came outside with a bucket, already knowing what lay ahead. She coaxed my grandmother through a long, violent spell of sickness while I left to pour a glass of water.

Inside, my impulse to help was immediately overshadowed by a desire to be as far away from the puke as possible.

Guilt tugged on my gag reflex.

I stood more uselessly than before, now from the other side of the door.

It had been nicer looking into a version of the past than out at this new reality. I had no idea if my presence would be soothing or cause embarrassment.

In between wretches, my grandmother spotted me holding her water.

“When did Jamie get so tall?” she asked.

My mom and I laughed.

I haven’t grown since I was 13.

We kept smiling, but I wondered if she knew how old I was. When had I stopped aging in her mind? When will I disappear for good?

I checked my phone and laughed harder.

“Mom,” I said, “It’s time to BeReal.”

The joke carried us through the next wave of vomit. I didn’t take the picture. This wasn’t a moment I’d be able to forget anyway.

Next week, my grandmother is moving into a home.

We already know she’s going to hate it.

She did a month-long trial last year and spent the whole time complaining, crossing each day off the calendar like a prisoner on death row.

It was the most effort she’s ever put into tracking time.

If her pride isn’t the last thing to go, it will be her stubbornness.

Even puking into a bucket on the ground, she would argue that she’s fine on her own. I have no idea if she actually believes herself, or if it’s a front.

When she finally stopped heaving, my dad lifted her into the house. He narrated the technique — her arms braced around his neck, his arms under her shoulders — as if it were a normal conversation.

“Just like a squat,” he said.

I couldn’t see anything familiar in the motion. I could barely see anything recognizable in my grandmother, either.

Her smell has become more rancid than she’d ever allow her right mind.

Her eyes sometimes glaze over.

Her face has sprouted new hair, which my mom can only groom between walking her dog, and cleaning her house, and doing her laundry, and picking up her meds, and grabbing her groceries and, and, and, and…

What is the same is The Chair my dad puts her in.

My grandma has been willfully rotting in the same spot since before she had a diagnosis.

A version of that chair has existed since I was little. It used to be a respite. Long days of gardening, painting, or shopping all ended in The Chair. Each new day started there, too.

When I was little, I brought all my prized possessions to The Chair. I would run up with pictures, grades, gymnastics moves, or new books for her to look at.

When I went shopping, The Chair was where the VIPs sat for my fashion show. The runway stopped at the full extension of the recliner.

“That outfit looks like grandma” was a common declaration from my mom on the nearby couch. I always took it as a compliment.

Slowly, The Chair became more and more of her day.

My mom and I moved out of my grandmother’s house when I was 14. She filled the quiet with the TV as background noise. Daytime talk shows blared as she sat in The Chair, eating, knitting, on the phone, or reading.

It morphed from a furniture piece to an entity.

As she settled back into The Chair, I noticed the same James Patterson paperback that was here during my last visit.

She’s been retracing the same few chapters over and over again. Stuck in the same place for years.

How depressing that her last book might be The President Is Missing.

My mom made up a plate of leftovers before we left. She covered it with plastic wrap and left a sticky note on top. A time stamp for when my grandmother was allowed to eat it.

“We don’t want you to get sick again,” she explained as she put the food in the fridge.

“Did I get sick?” my grandmother asked.

She grinned at me, oblivious to the whole ordeal from lunch. In her giant chair, with her frail body, she looked like the smallest thing in the world.

I wondered if that’s what she meant when she said I was tall.

All night, I thought about her alone in The Chair.

So many hours had passed.

What if she fell again?

What if she got sick?

Would she be able to make it to bed?

Would she remember to brush her teeth?

We went back first thing in the morning, and my mom looked at me as we braced ourselves in the driveway.

This is on her mind every day. My grandfather’s, too.

“I will never let you do this for me,” she said.

I bet my grandmother would have said that, too.

Now she’s making the move to the home a nightmare. What’s worse? Knowing she’s miserable, but safe? Or knowing she’s content, but at risk?

Inside, my grandmother had miraculously made it from The Chair to bed and back again.

The dog hadn’t had to go out yet.

The leftovers were still untouched.

We exhaled.

Another day mentally crossed off the calendar.

We sat around The Chair, and my mom held up new, presentable clothes for the home in a perverted version of my childhood fashion shows.

New pyjamas.

New undershirts.

New socks with little grips on the bottom for balance.

“Go-Fast Socks,” I said.

And the three of us laughed at a small memory we still shared.